Five years ago this month, the world shut down due to COVID-19. “Paris, Milan, London, New York, San Francisco, and even Delhi—even India, the entire country—locked down in the most dramatic deprivation of freedom, which we couldn’t have even imagined.” Government responses dramatically reduced the threat of COVID-19 but also eroded trust in public health officials. An ongoing measles outbreak in Texas and surrounding states and the threat of H5 bird flu are again raising the question of what steps the government may legitimately take to stop the spread of contagious diseases.

In a new essay, I offer a framework for answering that question: government public health interventions are legitimate only to the extent they minimize the amount of violence in society.

Nonconsensual transmission of dangerous pathogens is an inherently violent act. A virus or bacterium can be as deadly as a bullet or a blade. Government exists to prevent and to provide remedies to violence. Government may therefore intervene in public health for the same reasons it may justly act in other areas.

But only up to a point. Government public health efforts themselves introduce violence. Government achieves its ends through coercion—i.e., threats and the use of physical violence. Some public health measures are themselves coercive. Even taxes that fund otherwise noncoercive public health measures involve coercion. Government may legitimately intervene only if a given public health intervention would minimize the net amount of violence in society.

This approach allows significant scope for government public health activities. The successful campaign to eradicate smallpox passes the violence-minimization test with flying colors. New York State’s imprisonment of alleged typhoid spreader Mary Mallon does not. Some actions that governments took during COVID-19, notably subsidizing vaccines, pass the test. Many others, like slamming young men to the sidewalk for not masking, do not. Some interventions that initially passed the test failed it when effective vaccines became available.

Violence minimization is a more egalitarian and welfare-enhancing goal for public health officials than maximizing economic efficiency or even saving lives. It can also improve government public health efforts. To the extent government public health activities disregard autonomy, they can engender distrust and even resistance among civilians who see their own government as denying their equality by robbing them of autonomy. Prioritizing saving lives over autonomy can thus cause—and has caused—government public health efforts to backfire.

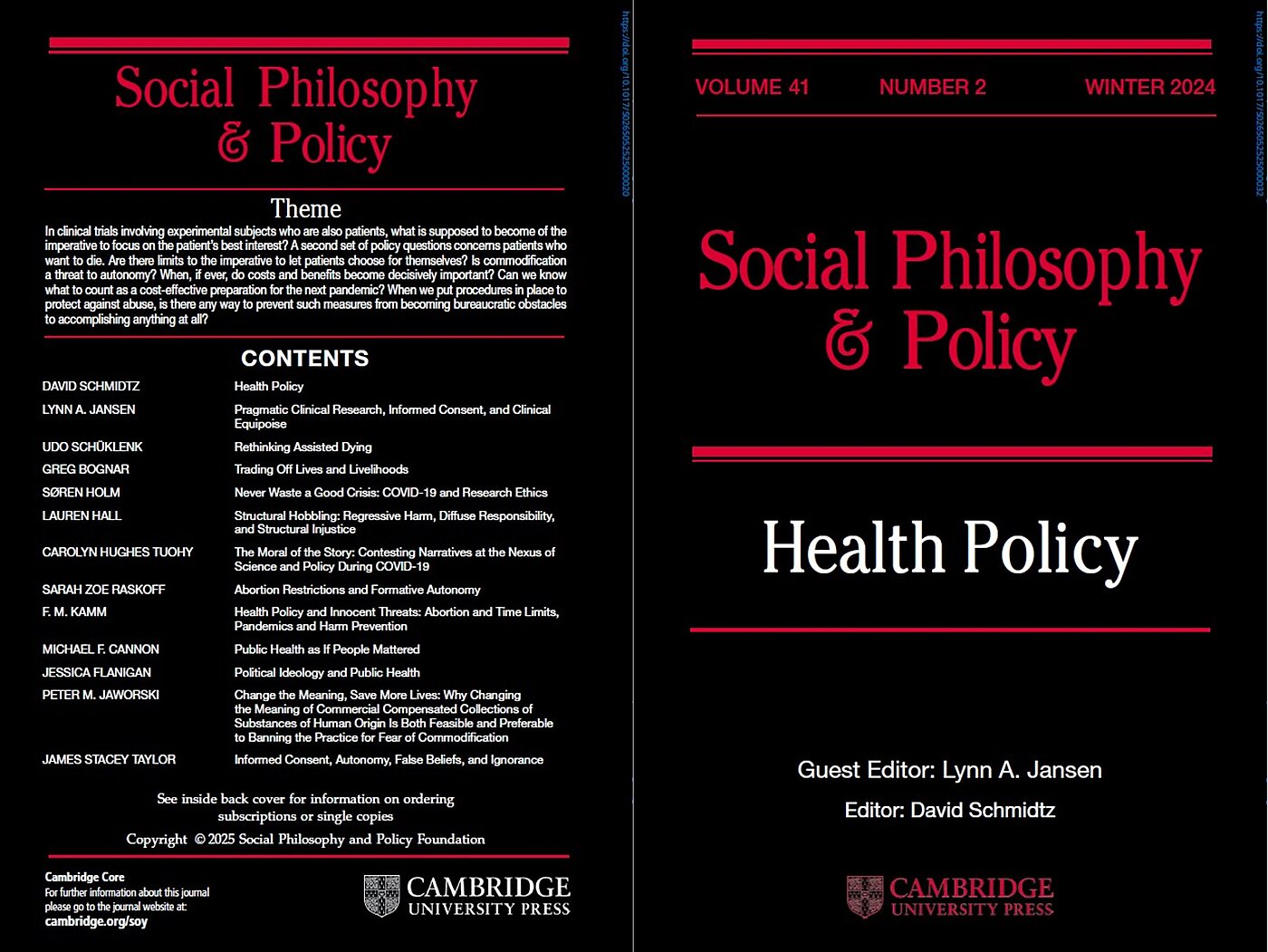

The essay, “Public Health as If People Mattered,” appears in the current issue of Social Philosophy & Policy (Cambridge University Press).