In 1954, the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation published a small book by Leland B. Yeager titled, Free Trade: America’s Opportunity. In it, he presents a concise but rigorous defense of free trade—both as a normative principle and a system that has a large net benefit to the world in terms of expanding the range of choices open to people and increasing the wealth of nations. This article provides a summary of some of Yeager’s key points that are relevant to current trade policy. (For a more detailed discussion of Yeager’s work, see Dorn 2018.)

The Normative Case for Free Trade

Yeager begins his book by presenting several value judgments that underlie the case for free trade:

- “That the well-being of individual human beings, as they themselves see it, is supremely desirable.”

- “That high and rising standards of living in terms of useful goods and services are an important element in human well-being (though not necessarily of overriding importance).”

- “That people should have as much freedom to run their own lives and businesses as is compatible with the freedom and well-being of others.”

- “That no group of people has a right, merely because of the occupation or industry in which its members work, to special favor from the government at the expense of the general public.”

In other words, people should be free to choose—that is, to pursue their happiness—provided they don’t violate the equal rights of others to their lives, liberties, and estates. This is the principle of freedom or what John O’Sullivan called the “voluntary principle.” Free trade presupposes a government of limited powers designed to protect persons and property, not one that restricts trade and caters to special interests. As Sullivan, editor of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, wrote in 1837, government “should be confined to the administration of justice, for the protection of the natural equal rights of the citizen, and the preservation of the social order. In all other respects, the voluntary principle, the principle of freedom, … affords the true golden rule” (see Dorn 2012: 637).

Yeager emphasizes that “free trade means letting people buy and sell as they see fit, abroad as well as at home.” In contrast, “protectionism means using the force of government to keep people from trading as they see fit or to fine them for it. Free trade does not force; it permits.” By harnessing government power to restrict free trade, protectionism diminishes individual freedom and expands government coercion.

The Positive Case for Free Trade

Every beginning student in economics learns that specialization, according to the principle of comparative advantage, and voluntary exchange lead to net benefits for society. Nations can consume more than they produce domestically, gain from the free flow of ideas that accompany global trade, safeguard against domestic supply shocks, and benefit from a wider range of choices resulting from open trade among nations.

Understanding the case for free trade requires “some abstract reasoning,” as well as “some ability to think clearly,” argues Yeager. Unfortunately, politicians are too often short-sighted and swayed to protect special interests, rather than adhere to the principle of free trade. The reality is that people can lose their jobs because of changes in consumer preferences, technology, and foreign competition. If the government tries to stop those forces from creating new opportunities and wealth, people eventually will lose both their personal and economic freedom as state planning advances.

Protectionist Arguments

Yeager lists a number of arguments protectionists use to justify government intervention in the conduct of foreign trade. They range from saving industries and jobs from unfair foreign competition and cheap imports to protecting infant industries and those necessary for national defense. While some arguments may have merit, none of them undermine the general case for free trade. They simply repeat fallacies that have long been exposed by rigorous economic thinking and empirical evidence.

The argument that is most relevant today pertains to the use of tariffs as a tool for retaliation and bargaining. President Trump is a champion of tariffs, which he believes are “beautiful” and will protect America from “unfair” competition. He sees them as a means for retaliating against countries like China who run large trade deficits with the United States.

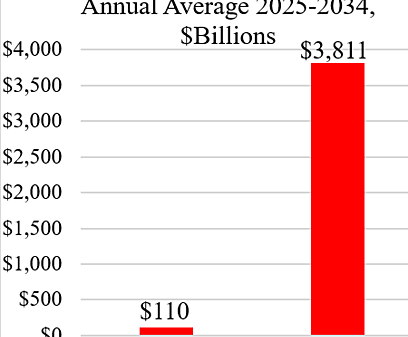

The problem is that tariffs, in effect, are instruments for committing economic suicide. US tariffs on Chinese imports are taxes on US citizens. Consumers pay higher prices for both foreign imports and US substitutes; industries that use component parts from China face higher costs; and the range of choices open to US consumers diminishes. While jobs in protected industries may rise, jobs elsewhere will decline, and overall economic growth and wealth creation will slow as protectionism takes hold. The same will occur in China if it retaliates by increasing its tariffs on US goods.

With a stroke of the presidential pen, Trump imposed tariffs totaling 145 percent on US imports of Chinese goods, and China responded by placing a prohibitory tariff of 125 percent on US goods entering the Chinese market. Due to pressure from the high-tech industry, the White House has temporarily exempted electronics and smartphones from the prohibitive tariffs. The president’s actions are creating tremendous uncertainty in global markets. Xi Jinping is correct in saying, “There is no winner in a tariff war” (see Bao 2025).

President Trump’s ultimate goal is not free trade; it’s to “make America great again” by being more self-sufficient and protecting American jobs. His tariffs are not reciprocal, they are meant to keep China out of our neighborhood. He fails to recognize that the purpose of free trade is not to create jobs, but to expand the range of choices open to people, and allow Americans to increase consumption beyond domestic production. Tariffs are not “beautiful,” they reduce economic and personal freedom, and stir crude nationalism.

US-China Relations

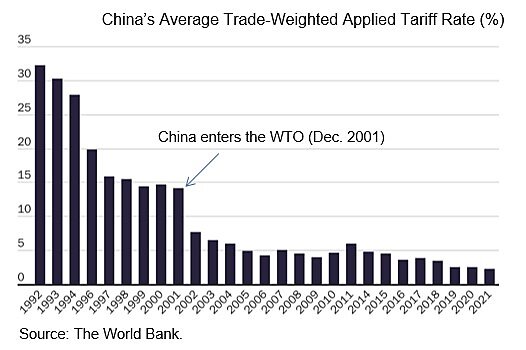

Prior to joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001, China unilaterally cut tariffs from more than 30 percent in 1992 to about 15 percent in 2000 (see chart). By 2021, China’s average trade-weighted applied tariff rate fell to slightly above 2 percent. As China liberalized its trade sector, along with other market-oriented reforms, its economy grew and people became more prosperous (see Drysdale and Hardwick 2018). President Trump and his advisers should not forget those facts.

Today, China has more than 55 million private companies that dominate the business landscape and account for more than 60 percent of GDP. In February, President Xi met with private entrepreneurs to encourage them to compete vigorously and promote “common prosperity.” He now recognizes the importance of the private sector in China’s future development and appears to be shifting away from his former embrace of state-owned enterprises. In December, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress will deliberate on legislation geared to further develop the private sector (Mo 2025).

Prior to the escalation of the current trade war, initiated by President Trump, Xi Jinping met with a high-level group of world business leaders in late March to emphasize that, “The essence of China‑U.S. economic and trade relations is mutual benefit and win-win cooperation.” Since 1978, China’s main goal has been “peaceful development” not trade-defeating tariffs. Xi is in favor of “an open world economy.”

Unilateral increases in tariffs—unilateral protectionism—by the United States diminishes the role of the WTO in bringing about a stable global trading order. According to Xi, “We must uphold the principles and rules of the WTO, continue advancing trade and investment liberalization and facilitation, and encourage all countries to expand the ‘pie’ of shared development through greater openness.” He told the CEOs, they should “speak with reason, act with pragmatism, firmly oppose retrogressive moves that turn back the clock of history, reject zero-sum thinking, and actively promote cooperation and mutual benefit.” Most eye-opening was Xi’s admonition not to “make decisions that defy market logic.”

Trump and his advisers downplay the progress China has made, and the fact that the United States has greatly benefited from China’s transition from autarky under central planning to market-based development and integration into the global economy. It is dishonest to blame China for many of America’s troubles. As Drysdale and Hardwick (2018: 567) note, most are due to “structural problems of the United States’ own making and their solution is in American hands alone. They require deep institutional and policy shifts and a different approach to social as well as international trade policy.”

Unilateral Free Trade

If multilateralism breaks down in response to retaliatory tariffs, then moving toward freer trade unilaterally should be considered as an option in place of stubborn negotiation and government planning. As Yeager writes, “While the United States would gain less by adopting free trade alone than as one free-trade country among many, it would still definitely gain.” Our resources would be more efficiently allocated than under protectionism, and we could reduce our foreign aid. Moreover, “free trade would show that Americans practice as well as preach their belief in free private enterprise,” argues Yeager.

Elon Musk is on the right track when he argues “that both Europe and the United States should move ideally … to a zero-tariff situation, effectively creating a free-trade zone.” Yeager would likely go further and say that the United States should unilaterally adopt a zero-tariff policy toward all trading partners, including China. Trump’s aversion to trade deficits and his impulse to protect American jobs by turning to prohibitive tariffs makes the odds of that happening dim.

In lieu of the difficulty of unilateral tariff reduction, Yeager accepts the idea that a country could use reciprocal trade agreements to liberalize foreign trade. These agreements differ from retaliatory tariffs, in which a country increases its tariffs as a bargaining strategy to incentivize foreigners to lower their tariffs. This is Trump’s hope, but it can backfire as foreigners retaliate by increasing their tariffs, which is what China has done in spades. As Yeager puts it, “With many countries maintaining or raising tariffs to get other countries’ tariffs down, the end result is likely to be an overall rise in trade barriers.… Tariffs for bargaining power boomerang.”

After examining alternative approaches to trade liberalization, he returns to his ideal, unilateral free trade:

If we Americans really want free trade, we can do better than just nibble here and there at tariff barriers by agreement with foreign countries. By adopting free trade independently, we can show the whole world that we consider tariff removal not as a kind of self-injury that must be carefully measured and paid for but as a benefit even to ourselves alone. Such a dramatic example would probably do more for the cause of world-wide free trade than thousands of reciprocal trade agreements.

The Role of Economic Education

Yeager places a great deal of attention on the role of economic education in creating and maintaining a free society. In particular, politicians, opinion leaders, and the public need to gain a firmer grasp of free-trade principles and the high cost of protectionism. As a teacher, he argues:

The case for free trade and the exposure of protectionist fallacies must be repeated again and again in such simple words that understanding gains a foothold outside academic circles. Such an understanding will drive home the all-important point that the clash of interests in tariff matters is not between Americans and foreigners but between each of various special producer groups on the one hand and the American people as a whole, whose losses from protectionism far outweigh the gains to special groups, on the other hand.

If enough people understand the principle of comparative advantage, the gains from trade, and the relation between economic and personal freedom, the chances for free trade will improve. We can then celebrate a true “Liberation Day” as opposed to Trump’s pseudo-liberation.

China learned the hard way that autarky has a high cost. Zhao Ziyang, in his book Prisoner of the State (2009: 137) observed:

The result of doing everything ourselves was that we were not doing what we did best. We suffered tremendous losses because of this. I now realize more and more that if a nation is closed, is not integrated into the international market, or does not take advantage of international trade, then it will fall behind and modernization will be impossible.

That lesson should not be lost on Trump and his advisers. The best way to make America great again is to adopt the principle of free trade to show the Chinese people and the world that limited government and free enterprise under a just rule of law is the path to human dignity and progress. Leland Yeager’s 1954 book is one of the best guides for that journey.

James A. Dorn is Senior Fellow Emeritus at the Cato Institute.