Newly inaugurated Mayor Zohran Mamdani last week promised New Yorkers that he would “replace the frigidity of rugged individualism with the warmth of collectivism.” He knows what he’s doing in setting up this dichotomy. “Collectivism” is not a slip of the tongue or a vague moral appeal to kindness. It is a loaded ideological term with a long, well-documented pedigree and an even longer rap sheet.

By collectivism, political theorists and its own champions have meant a social order in which the claims of the group—often defined and enforced by the state—override individual choice, property rights, and voluntary exchange. Production and distribution are guided not by prices and consent but by political priorities, and individual autonomy is tolerated only insofar as it serves collective ends. That is not a caricature; it is the standard definition of what’s espoused in fascist, socialist, and communist literature.

The word’s lineage matters. Zohran Mamdani is consciously drawing on a tradition that stretches from Karl Marx, who rejected “bourgeois individualism” in favor of collective ownership, through Vladimir Lenin, who implemented it via one-party rule, to Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, who enforced it at colossal human cost. Even outside the communist tradition, collectivism was proudly embraced by Benito Mussolini, who defined fascism as the negation of individualism in favor of the state as an ethical whole, and by strongmen such as Idi Amin, who expelled ethnic minorities and appropriated their land in the name of the national good.

The historical record is not ambiguous. Where collectivism has moved from rhetoric to reality, the results have been grim. The Soviet Union’s collectivized agriculture led to chronic shortages and mass famine through both disastrous economic policies and by design to suppress dissent. China’s Great Leap Forward killed tens of millions. Cambodia’s agrarian collectivism under Pol Pot destroyed a quarter of the population, resulting in the “killing fields” and perhaps the most brutal regime in modern history. In each case, politics replaced price signals, error correction was treated as dissent, and individuals weren’t free to exit the collective.

The disastrous results were not accidental policy errors. They followed directly from replacing decentralized decision-making and consent with ruthless political command.

Defenders respond that Mamdani doesn’t mean that kind of collectivism. He’s aware of the dignity that comes with consent and means only to foster solidarity and community—rule by a velvet glove rather than an iron fist. In this reading, his intervention is just reheated Barney Frank—the idea that “Government is simply the name we give to the things we choose to do together.”

But this rhetorical pivot is precisely the trick. Many New Yorkers didn’t choose rent control or nationalized grocery stores. Taxes are non-optional, but I’d bet most New York taxpayers would prefer to keep their money rather than subsidize free buses or childcare. Truly voluntary cooperation between free people for a common goal is great, but it already has a name: civil society.

Individualists don’t pretend to be islands, which is why Mamdani’s jab at “rugged individualism” is a strawman. In modern life, nearly everyone depends on food grown by others and often prepared by others, too. That cooperation is possible only when individual choice and consent are respected. The farmer or cook parts with what they’ve produced only when compensated fairly or out of voluntary kindness and generosity.

Likewise, non-market institutions like mutual aid, charities, families, religious groups, cooperatives, and more are bottom-up institutions grounded in consent. They arise in a framework where individuals are free to cooperate and pursue shared goals on their own terms.

Collectivism, by contrast, is top-down. It inevitably requires someone to decree what the collective wants and to compel compliance from dissenters. To override the farmer’s consent—to steal from him because others claim they want it more—requires collectivism. The supposed “warmth” is a rhetorical sugar coating for using coercive power to do things free individuals would choose otherwise not to do. Things like transitioning private property into a “collective good,” as Mamdani’s director of the Office to Protect Tenants advocated for in a newly resurfaced clip.

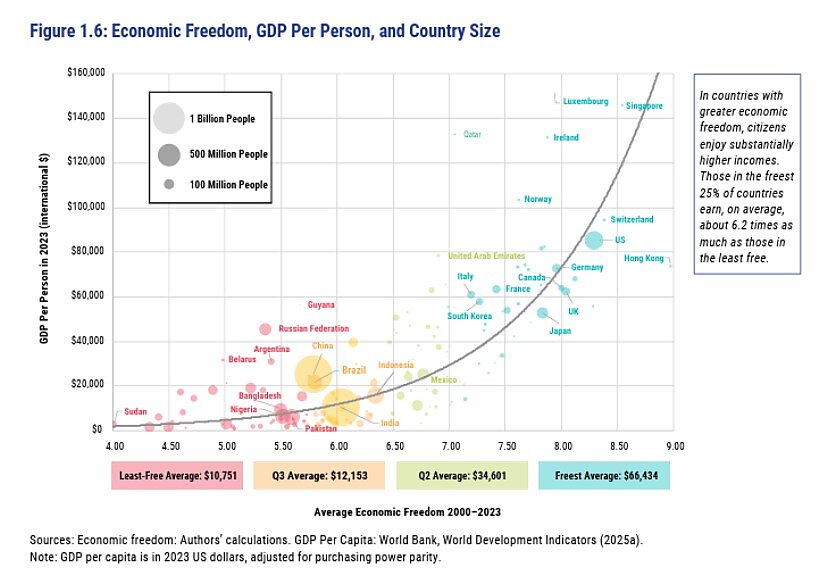

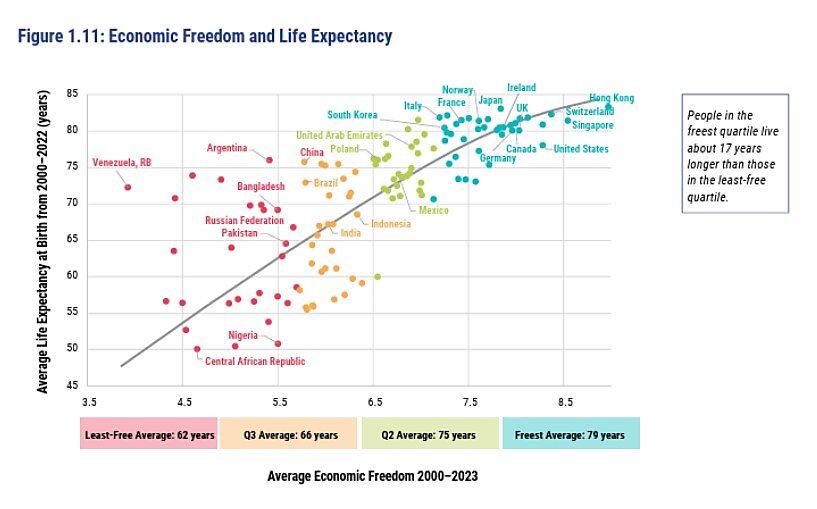

This overriding of individual freedom has an economic cost. Countries that most fully rejected collectivist economics—those that protect private property, free prices, and open exchange—are dramatically richer, healthier, and longer-lived than those that embraced state control. That much is clear in the 2025 Economic Freedom of the World report. Those in the freest 25 percent of countries earned, on average, 6.2 times as much as those in the least free. Poverty rates are 25 times greater in the least free countries, even while those countries worked 20 percent more, on average. Meanwhile, in the most economically free countries, people live about 17 years longer, infant mortality is one-tenth what it is in the least free countries, and people even report higher levels of general life satisfaction.

These differences aren’t cultural but institutional. The yawning differences in quality of life and personal incomes between East and West Germany, North and South Korea, or pre- and post-reform China emerged among people with the same language, culture, and history only after institutions divided on collectivism and individualism. Thirty years after reunification, in the case of Germany, GDP continues to lag in the formerly collectivist states.

There is also, more importantly, a moral cost. Collectivism robs individuals of autonomy. Instead, people are treated as a means to an end—to produce as the state dictates. In short, to become modern-day Stakhanovites, the selfless workers who supposedly devoted themselves to the Soviet cause, but who we now know were largely fictional tools of Stalinist propaganda.

Libertarianism begins from the opposite premise: people own their lives. They are entitled to choose, trade, associate, and experiment—even to fail—without needing permission from a planner or politician. That moral foundation and the pluralism it produces are not cold or atomistic. It is what makes genuine cooperation possible and, for most people, what makes life worth living.