Jeffrey A. Singer and Bautista Vivanco

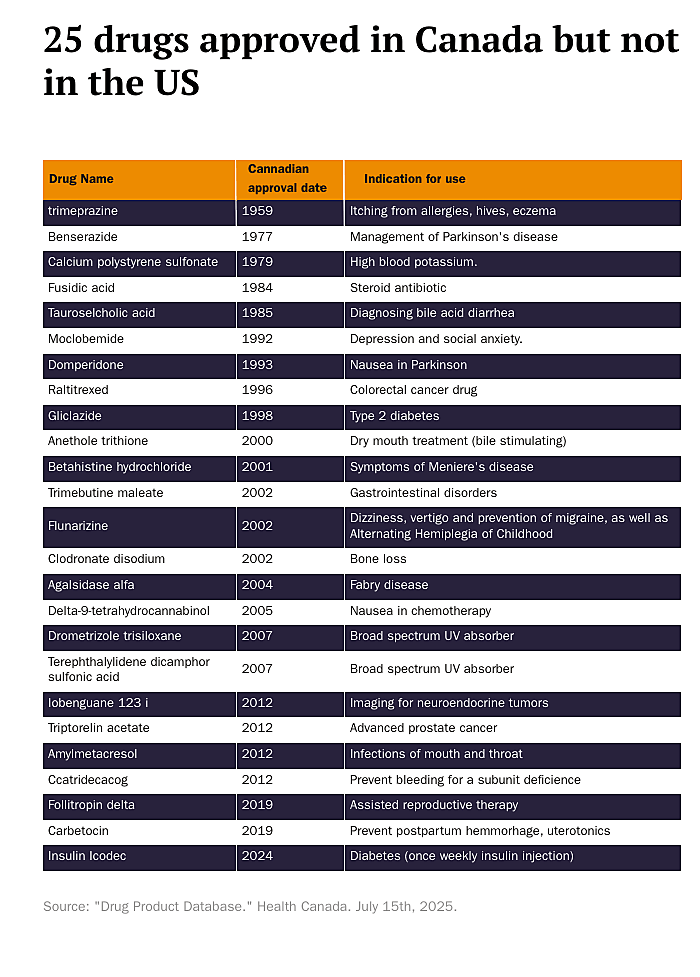

Earlier this month, STAT News published an opinion piece we wrote about the drug domperidone, an anti-nausea medication that may also help with breastfeeding. It is available by prescription in Australia, Canada, the UK, and several European Union countries, over the counter in China, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, and South Africa, and either OTC or by prescription in at least 58 countries—but only horses can obtain it in the US. Americans can drive across our northern or southern borders if they wish to access domperidone. Canadians have been able to access domperidone since 1993.

This led us to ask: what other drugs does the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) block patients and doctors from accessing that Canadian patients and doctors can get? To address the question, we compared the contents of the American Drugs@FDA database and the Canadian Drug Product Database. These government-run databases provide the most current information on the approval status of most drug products in these two countries. We identified 69 drugs that have received market approval in Canada but not in the US.

One is benserazide, which is paired with levodopa to treat Parkinson’s Disease. Benserazide is on the World Health Organization (WHO) list of essential medicines. The European Medicines Agency designated it an “orphan drug” due to its potential to treat the blood disease beta-thalassemia. The FDA blocks Americans from accessing the drug, even though it has been widely used for decades—since 1977 in Canada—because its manufacturer, Roche, chose not to incur the costs of the clinical safety and efficacy trials the FDA would require.

Another is raltitrexed (Tomudex), which Canadians have been able to access since 1996. Oncologists use the chemotherapeutic agent 5‑fluorouracil (5‑FU) as adjuvant (post-surgical) therapy for patients with colorectal cancer or to palliate patients with advanced disease. Because it is equally effective, doctors in Canada and many European countries substitute raltitrexed for 5‑FU in patients who develop 5‑FU toxicity, which can involve the heart and the mucous membranes. The FDA expects comprehensive clinical trial data involving US or multi-regional patient populations to evaluate safety and efficacy. Historically, most raltitrexed studies were carried out in Europe. Once again, there is little motivation for AstraZeneca, the manufacturer of the drug, to incur the costs. Fortunately, the FDA removed restrictions, allowing Americans to access the drug capecitabine (Xeloda) as an alternative to 5‑FU for adjuvant therapy. However, the body metabolizes capecitabine into 5‑FU, making it a less effective substitute for patients with 5‑FU toxicity.

Health Canada approved agalsidase alfa (Replagal) in 2004 as an enzyme replacement therapy for people with Fabry’s Disease, a rare X‑linked disorder where individuals lack an enzyme that causes glycolipid deposits in multiple organs, leading to multisystemic disease. Patients in Europe and Japan also have access to this drug. The manufacturer, Shire (now Takeda), submitted a Biologics License Application (BLA) to the FDA in December 2009. It withdrew the application in 2012 because the FDA required additional clinical trials. The FDA did not raise safety concerns about Replagal but requested more comprehensive clinical data to demonstrate efficacy and safety in a US setting. Without meeting these requirements, Shire decided to withdraw the application instead of investing in new trials.

Fortunately, Americans with Fabry’s Disease have access to another drug, agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme). While no studies compare the two drugs, there is no evidence that one is superior. Nonetheless, health care consumers would benefit from the choice and competition between them.

Also among the 69 drugs is insulin icodec. The world’s first once-weekly insulin injection is approved in Europe, Canada, Australia, Japan, and China, giving patients freedom from daily shots. The FDA, however, withheld approval after its Advisory Committee argued that evidence did not show weekly dosing’s benefits outweighed hypoglycemia risks in type 1 diabetes. (Instead of autonomous, adult patients, a bureaucratically-appointed panel got to weigh the risks versus the benefits.) The manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, proposed safeguards—limiting use to adults with low glycemic variability, requiring continuous glucose monitoring, and adjusting bolus insulin labeling—but the FDA still rejected it. As a result, American diabetics remain among the few in the developed world denied access to a weekly insulin analogue that could reduce treatment burden and improve quality of life.

An astute reader might ask why we haven’t mentioned sunscreens. As explained here, Asians, Australians, and Europeans can buy sunscreens that are more effective at preventing skin cancer than those sold in the United States. This is because their regulators classify sunscreens as cosmetics rather than drugs. Canada, like the US, classifies sunscreens as over-the-counter medicines. Canada approved drometrizole trisiloxane and terephthalylidene dicamphor sulfonic acid—both offering more effective UVA protection than sunscreens in the US in 2007. The FDA, by contrast, hasn’t approved a new active sunscreen ingredient since 1999.

The table below lists 25 of the 69 drugs Canadians can access that the FDA prevents Americans from using, along with the years they became available and their medical indications. Many of these drugs are used to treat cancer or rare diseases, but a number of them treat common conditions such as Type 2 diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and even dry mouth.

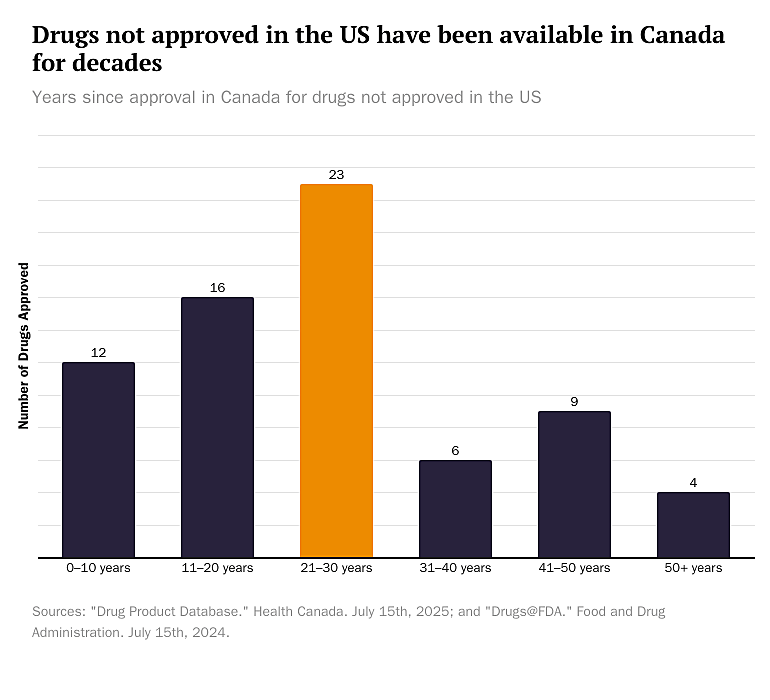

The bar graph below shows the different lengths of time Americans have gone without access to 69 medications that Canadians can obtain. We estimate that the average number of years Canadians have had access to these medications while the FDA has barred Americans from using them is 25.5 years—if we exclude canine and equine Americans.

Why exclude them from the average? Canadians have been using trimeprazine, an antihistamine that treats severe itching caused by allergies, hives, chickenpox, insect bites, and other conditions, since 1959. In 2024, the FDA finally allowed dogs in the US to benefit from it. However, even some cats have benefited when veterinarians prescribed it off-label despite FDA guidelines.

Health Canada approved hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) in 1976 to treat intestinal spasms, gallbladder, and renal colic. In 2004, the FDA approved it, but only for horses. Also, in 2010, American horses got relief from nausea when the FDA approved domperidone—for them, not us.

The white paper Drug Reformation and chapters 4 and 5 of the book Your Body, Your Health Care, both published by Cato, explain how the FDA infringes on adult autonomy, including the right to self-medicate, by establishing a government monopoly over decision-making regarding which medications adults can use and under what conditions. Before Congress passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, many private third-party organizations played a key role in evaluating, vetting, and certifying medicines for safety and effectiveness. To this day, professional medical and scientific societies continue to review research literature and assess alternative, off-label uses of FDA-approved drugs that the FDA does not restrict clinicians from prescribing.

Both sources explain how the rigid and cumbersome FDA approval process causes both drug lag and drug loss. Drug lag describes the situation where seriously ill people suffer and even die while waiting for the FDA to approve a drug that might already be available elsewhere. It is especially cruel to terminally ill patients, as it deprives them of the right to try to save their lives with drugs that have already proven safe but are still waiting for efficacy approval. Many severely ill Americans die while waiting for the FDA to approve drugs that regulators in other countries have already authorized.

In a 2020 Cato blog post, former Cato research associate Jalisa Clark explained how drug lag led to civil disobedience among AIDS activists in the late 1980s and inspired the “Right to Try” movement, which ultimately resulted in Congress passing the “Right to Try” Act in 2018.

Drug loss occurs when pharmaceutical companies decide not to pursue promising treatments because the high cost of FDA approval makes it unlikely they will recover their investments. By shutting the door on these possibilities, the approval process not only limits what manufacturers can bring to market but also restricts patients’ freedom to choose their medicines.

Drug lag and drug loss are hidden effects of the FDA’s regulatory monopoly.

We recognize that replacing the FDA’s centralized regulatory model with a decentralized system led by private organizations and supported by civil tort law faces formidable political hurdles. However, the political difficulties do not lessen the urgency for reform, as the current system hinders innovation, raises costs, and ultimately prevents patients from accessing potentially life-saving treatments.

In our STAT News column, we present an intermediate proposal that promotes incremental reform by increasing patients’ options and access to medicines: international drug reciprocity.

To move toward restoring autonomy, Congress should enact reciprocal approval for drugs and medical devices cleared by comparable countries. The CE mark, for example (from the French term “conformité européenne,” translated as “European conformity”), indicates that a product meets European Union safety standards. E.U. member states Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway already recognize one another’s approvals. Since 2018, Australia has allowed access to FDA-approved medical devices, and E.U.-authorized ones for even longer. Israel permits its residents to utilize drugs and devices approved by the governments of the United States, European Union, Australia, and Canada.

Our investigation focused on drugs available to Canadians that the FDA prohibits Americans from accessing. We identified 69 drugs that Canadians have been obtaining for about 25 years on average. It’s easy to imagine that removing barriers to drugs approved in other comparator countries like Australia, Canada, the European Union, Israel, Japan, and Switzerland could improve access to dozens, if not hundreds, of additional medicines.

The FDA’s regulatory monopoly blocks Americans from accessing treatments that are already proven safe and effective in other countries. By adopting international reciprocity, we can lift this unnecessary restriction and give patients more power to choose their medicines—because no one should need a passport to get the care they need.